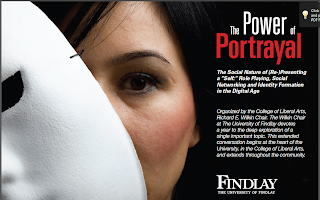

I thought it made sense to place the print marketing materials up on the Power of Portrayal blog. If you haven't been to the UF campus recently and/or haven't received one of these in the mail, this is what they look like:

I suppose it's relevant to our theme to mention that the template in Blogger does not allow for PDF attachments, so I used a screen capture program to reconfigure these files and then upload them on the blog. This process reminded me of two relevant/related issues to considering how content is created/manipulated in digital environments in 2012:

1) Templates ("seamless" layered manifestations of what we now know as Web 2.0) cloak the struggles that early pioneers of the Internet faced when creating their digital spaces. In Web 1.0, bandwidth, technology and memory restrictions limited digital authors. Early web "autobiographers," e.g., Justin Allyn Hall (“Justin's Links from the Underground”) http://www.links.net/vita/ , used HTML encoded text to create their dynamic personal websites. These early Web 1.0 authors, by necessity, had a general knowledge of HTML code and an understanding of its limitations.

For example, imagine a web author like Hall writing his digital autobiography in January 1994 before web-design computer programs such as Adobe Dreamweaver were available. Hall decides that he wants a simple webpage—a header and three short sentences to appear on the computer monitor as follows:

Justin’s Self

Reflection

Justin is

bold

Justin

is big

Justin

is under and over

<html>

<body>

<h1>Justin’s

Self Reflection </h1>

<font

size=“2” face=“Times New Roman”>

<p><b>

Justin is bold</b></p>

<p><big>

Justin is big</big></p>

<font size=“2” face=“Times New Roman”>

<p>

Justin is<sub> subscript</sub> and

<sup>superscript</sup></p>

</body>

</html>

Since “WYSIWYG” (what you see is what you get) web-authoring

programs including Dreamweaver do not

exist in January 1994, everything Hall writes has to be manually coded. If he

wants just the words “Justin

is bold” on his webpage, he has to type “<html> <body>” to begin his

page, “<font size=“2” face=“Times New

Roman”>” to use 12 point, Time New Roman font, “<p><b> Justin is

bold</b></p>” to place the text in bold, and “</body>

</html>” to finish the page. In other words, all of the basic formatting functions

Web 2.0 authors assume are transparent and seamless were part of a laborious web

authoring process that acted to discourage the less committed and less

technologically savvy autobiographers.

The increasing

availability of Web 2.0 technological features after the year 2000, however, made

the process of web authoring much more user-friendly. These features provided

online autobiographers with an opportunity to circumvent coding in HTML if they

wished. Sophisticated web-design programs, Dreamweaver, etc., with their convenient screen

templates and relatively easy learning curves encouraged more people to

consider constructing their own pages because knowledge of HTML coding was no

longer a prerequisite skill. In some ways, these programs replicate the basic functions

of universally popular word processing programs like Microsoft Word allowing for a transfer of skills

from one well-known computer program (Word)

to a lesser-known computer program (Dreamweaver).

AND

2) To say I uploaded "print" marketing materials for the Power of Portrayal is a misnomer at best. The postcard above was born digital. The text was drafted in Microsoft Word, the photo was taken with a digital camera, and the design and layout was created in Adobe InDesign. The print product is now only a manifestation of the original digital process and finished product. This is not terribly profound in and of itself. We have been creating text and most other media through digital means for the better part of the last two decades. This technological progression (and let's be clear, this does not mean technological determinism), however, has in many ways disrupted not only the primacy and ethos of print as a privileged form of media, but it has also permanently changed what we expect from our media experiences on both the producing and consuming ends of the spectrum.

To give this a bit more perspective, in The

Gutenberg Galaxy (1962), Marshall McLuhan observed that every communication

medium or technology including alphabets, printing presses, and speech affects

the expression of thought through language. McLuhan’s protégé and eventual

critic, Walter Ong, noted in Orality and

Literacy (1982), the transformation from speech to writing that took place

several thousand years ago removed text from the world of sound and

“reconstituted the originally oral spoken word in visual space” (121). And the

shift from the handwritten manuscripts of the Middle Ages to the mechanically

produced printed books of the fifteenth century, meticulously detailed by

Elizabeth Eisenstein in The Printing

Press as an Agent of Change (1980), effected widespread cultural changes

including the preservation of knowledge, the accumulation of information, and

the widespread dissemination of ideas in a cheap and efficient manner.

Certainly, technological transformations of text are not new phenomena

exclusive to the current age of digital media. As language gravitated first

from the spoken word to crude stone tablets, from stone tablets to papyrus

scrolls, from papyrus scrolls to the handwritten codex, and eventually from

codex manuscript to the printed book, each successive “technologizing”[i]

of the word altered the relationship between the speaker (writer) and the

audience (reader). The migration of text from print to a digital format is the

latest of these textual transformations.

No comments:

Post a Comment